Dark Energy Survey census of the smallest galaxies hones the search for dark matter

Observations of dwarf galaxies around the Milky Way have yielded simultaneous constraints on three popular theories of dark matter.

A team of scientists led by cosmologists from the Department of Energy’s SLAC and Fermi national accelerator laboratories has placed some of the tightest constraints yet on the nature of dark matter, drawing on a collection of several dozen small, faint satellite galaxies orbiting the Milky Way to determine what kinds of dark matter could have led to the population of galaxies we see today.

The new study is significant not just for how tightly it can constrain dark matter, but also for what it can constrain, said Risa Wechsler, director of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC) at SLAC and Stanford University. “One of the things that I think is really exciting is that we are actually able to start probing three of the most popular theories of dark matter, all at the same time,” she said.

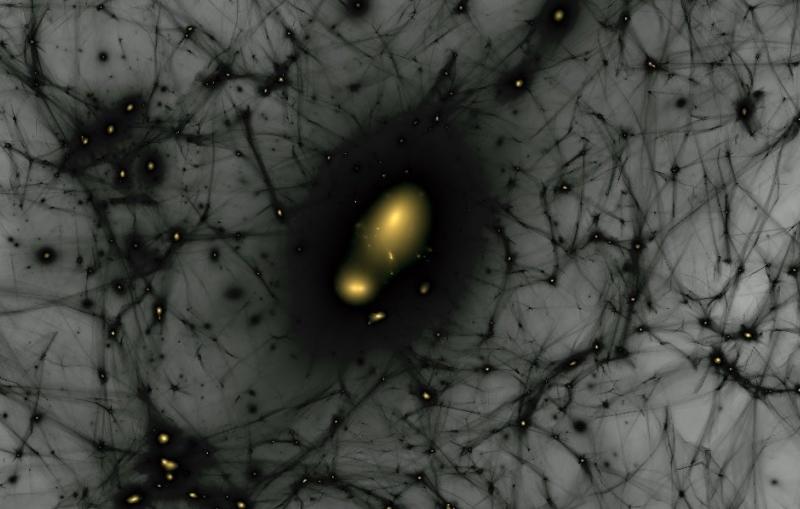

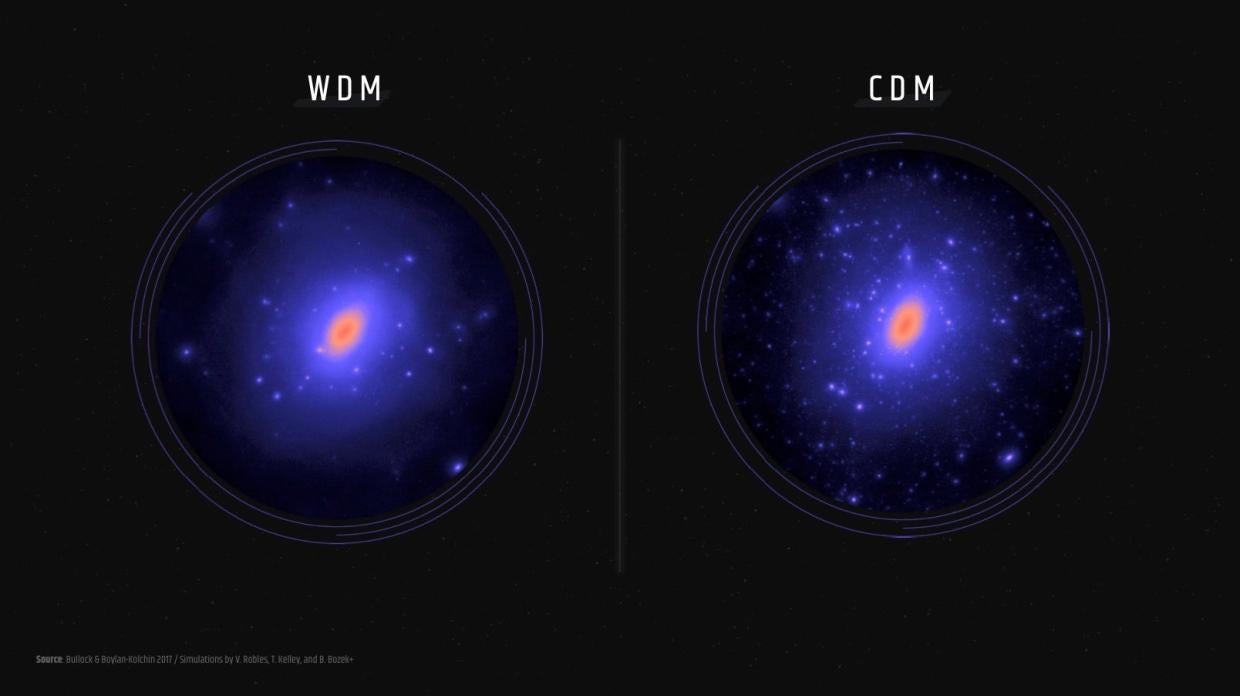

Dark matter makes up 85 percent of the matter in the universe and interacts very weakly with ordinary matter except through gravity. Its influence can be seen in the shapes of galaxies and in the large-scale structure of the universe, yet no one is sure exactly what dark matter is. In the new study, researchers focused on three broad possibilities for the nature of dark matter: relatively fast-moving or “warm” dark matter; another form of “interacting” dark matter that bumps off protons enough to have been heated up in the early universe, with consequences for galaxy formation; and a third, extremely light particle, known as “fuzzy dark matter,” that through quantum mechanics effectively stretches out across thousands of light years.

To test those models, the researchers first developed computer simulations of dark matter and its effects on the formation of relatively tiny galaxies inside denser patches of dark matter found circling larger galaxies.

"The faintest galaxies are among the most valuable tools we have to learn about dark matter because they are sensitive to several of its fundamental properties all at once," said Ethan Nadler, the study’s lead author and graduate student at Stanford University and SLAC. For instance, if dark matter moves a bit too fast or has gained a little too much energy through long-ago interactions with normal matter, those galaxies won’t form in the first place. The same goes for fuzzy dark matter, which if stretched out enough will wipe out nascent galaxies with quantum fluctuations.

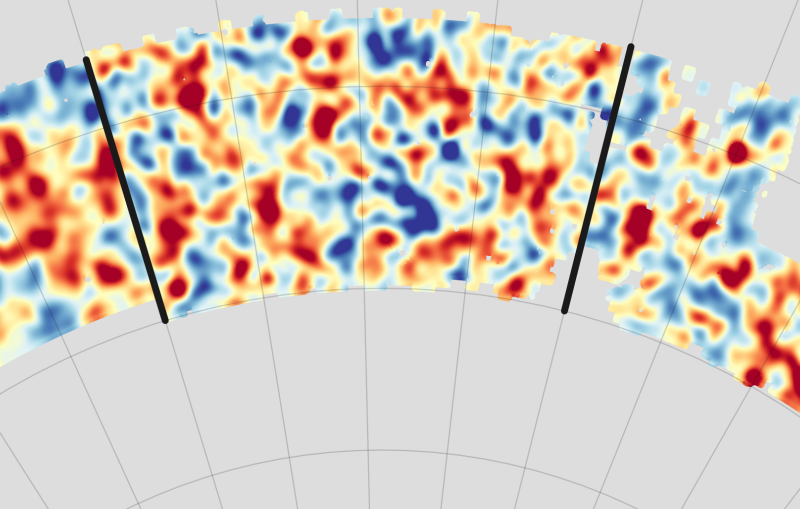

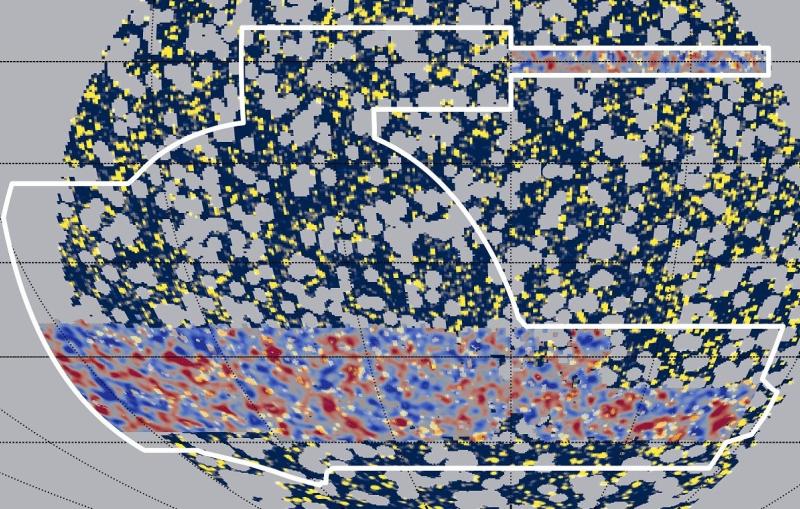

By comparing such models with a catalogue of faint dwarf galaxies from the Dark Energy Survey and the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System, or Pan-STARRS, the researchers were able to put new limits on the likelihood of such events. In fact, those limits are strong enough that they start to constrain the same dark matter possibilities direct-detection experiments are now probing – and with a new stream of data from the Rubin Observatory Legacy Survey of Space and Time expected in the next few years, the limits will only get tighter.

"It’s exciting to see the dark matter problem attacked from so many different experimental angles," said Fermilab and University of Chicago scientist Alex Drlica-Wagner, a Dark Energy Survey collaborator and one of the lead authors on the paper. “This is a milestone measurement for DES, and I’m very hopeful that future cosmological surveys will help us get to the bottom of what dark matter is.”

Still, said Nadler, “there’s a lot of theoretical work to do.” For one thing, there are a number of dark matter models, including a proposed form that can strongly interact with itself, where researchers aren’t sure of the consequences for galaxy formation. There are other astronomical systems as well, such as streams of stars that might reveal new details when they collide with dark matter.

The research was a collaborative effort within the Dark Energy Survey. The research was supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Fellowship, by the Department of Energy's Office of Science through SLAC, and by Stanford University.

Editor’s note: this article is based on a press release from Fermilab.

Citation: Ethan Nadler et al., available as an arXiv preprint (http://arxiv.org/abs/2008.00022)

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.